I recently led a class on action research quality which motivated me to write up a summary answering the question: What does good quality action research look like?

This is not a straightforward question with a single answer since there are different types of action research. For example, Carr and Kemmis (1986) identified three different types – practical, technical or critical, concerned with developing practitioners, achieving outcomes, or addressing injustice. Over the decades, writers have suggested that quality is not a simplistic judgement and holistic approaches are needed. While debates go on (and I have been part of that debate – see Arnold and Norton, 2023), I wanted to offer something practical as a starting point for practitioners in this space.

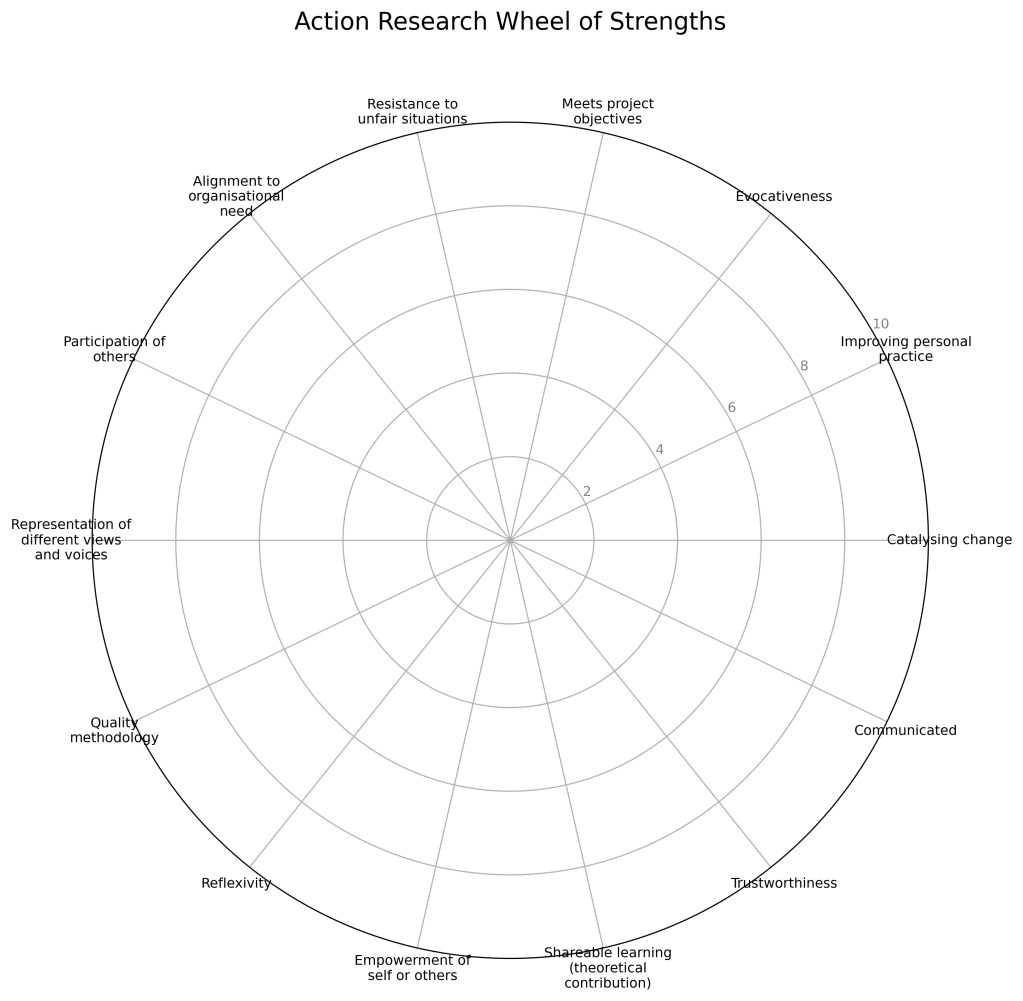

A review of literature has led me to 14 markers of quality though I suspect there will be others. This is not meant to be a checklist whereby one aspires to a score of ‘a perfect 10’ across all areas. Consider it a quality tool for reflection rather than a quality checklist (more on how to use it later).

Here are some possible markers of quality (there is no order of priority given):

- Catalysing Change: Does the work energise others to bring about further change? This relates to the concept of catalytic validity (Hope & Waterman, 2003; Nehez, 2024).

- Trustworthiness: Is the research clear and transparent in its decision-making at each stage?

- Improving Personal Practice: Did the research prove to be a practice-changing practice? Asking, like Kemmis (2009), whether it changes people’s patterns of ‘saying’, ‘doing’ and ‘relating’?

- Evocativeness: Does the research result in evocative accounts that are relatable and which provoke a response? (see Heikkinen et al., 2007 for a substantive exploration of evocativeness).

- Meets Project Objectives: Did the project accomplish what it set out to do? (see Bradbury et al., 2019; Newton & Burgess, 2008).

- Resistance to Unfair Situations: Does the work offer a critical voice or action to counter unfair or disadvantageous conditions?

- Alignment to Organisational Need: Does the project address an organisational need or broader concern rather than a personal “pet” issue? (for a consideration of the role of action research in organisations see the work of Coghlan (2019).

- Participation of Others: Were others meaningfully involved (e.g., students, colleagues, employers, community members)? Participation is widely advocated in action research (see, for example, Norton, 2009). Jensen and Diklitas’ (2023) review shows that all participation is not equal; they offer different categories of engagement with students in pedagogic action research, and these may be transferable to other stakeholders too.

- Representation of Different Views and Voices: Did the research seek out diverse or marginalised voices, and not just convenient ones?

- Quality Methodology: Was the study methodologically sound, using appropriate and well-applied methods (e.g., interviews, mixed methods)? Lin Norton and I debated the importance of methods in pedagogic action research in our collaborative paper (Arnold & Norton, 2021).

- Reflexivity: Did the researcher critically review their own decisions and learning, adjusting their path and identifying lessons learned? And in the terms of Cornish et al. (2023) did they reflect on their own positionality? Reflexivity is widely cited as important to action research (see for example: Arnold & Norton, 2018; Heikkinen et al., 2007)

- Empowerment of Self or Others: Did the research give a more confident voice to the researcher or to the participants? Particularly anyone whose voice may previously have been excluded.

- Shareable Learning (Theoretical Contribution): Does the research offer lessons or insights that others can meaningfully use? Please note sharing learning is not synonymous with generalisation. The importance of theory emerging from research is emphasised by Arnold and Norton (2018),

- Communicated: Has the research been communicated and open to peer scrutiny? For communicative validity see work by McNiff (2013) and for emphasis on dissemination and sharing see Norton (2009) and for consideration of dialogic, rather than traditional, approaches to dissemination of action research see Canto-Farachala & Larrea (2020). Quality in communication may depend on engagement, reach, scrutiny, and clarity of message, amongst other things.

Please note, items 9. 11, and 12 all link in to the overarching idea of emancipation in action research (see for example Riedy et al., 2023).

With some AI co-creation (Chat GPT) I have turned my list into a model to allow a visual self-assessment of the quality markers. On the wheel below, individuals can rate their work on a scale of 1-10. Because each project will be shaped so closely by the intentions of the researcher, the operating context, and practical constraints, as well as the wishes and influence of stakeholders or participants, it is not the case that a lower score in one or another category means that the research is poor quality. This self-assessment should simply help identify the key strengths in a specific research project while triggering discussion or reflection on lower-scoring areas. It is a tool for reflection to prompt a holistic assessment.

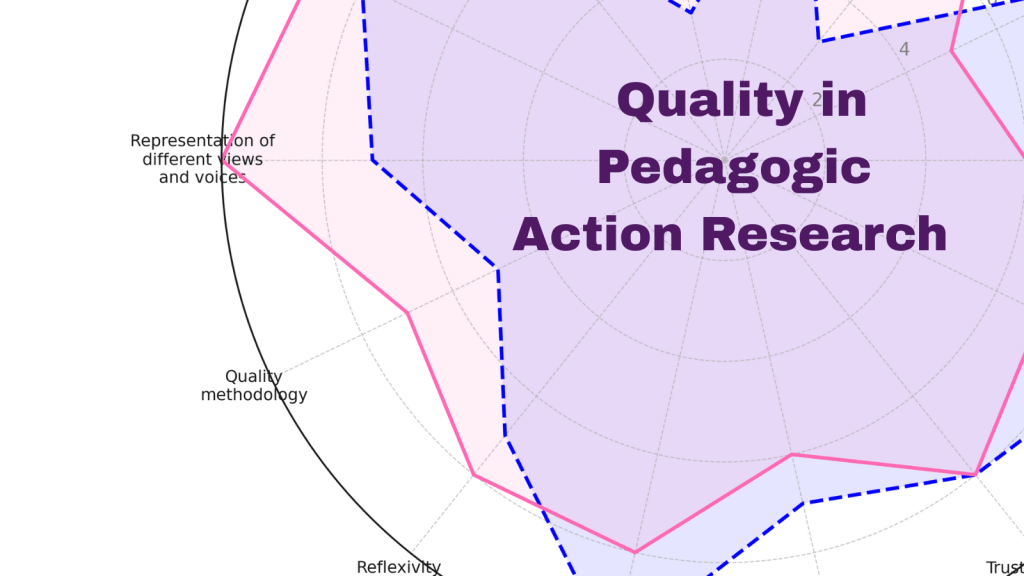

The completed chart below shows an example of two different (imaginary) pieces of Pedagogic Action Research. Neither is better than the other – they are simply different. For the pink (solid) line I brought to mind a project which is about story-telling – capturing different voices of a type of student experience to foreground challenges and diverse experiences – such a project may simply be called Experiences of being a politics student in times of change. The blue line represents a different type of project where an intervention is made to introduce professional development on the topic of active learning; the intervention creates change and builds momentum for discussion around engaging teaching and develops broadly sharable lessons which may be useful to others. These two fictitious examples seek to highlight the quality profiles that different types of projects will have.

Perhaps different types of action research display similar quality profiles—but that’s for another day! There’s more work to do here in breaking down each criterion to explain the characteristics of strength, but hopefully, this is a starting point for considering features of quality that may apply to pedagogic types of action research. Please feel free to post any thing that should be added or deleted, and wider feedback is always welcome.

Arnold, L., & Norton, L. (2018). HEA Action Research: Practice Guide. HEA. https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/action-research-practice-guide/

Arnold, L., & Norton, L. (2021). Problematising pedagogical action research in formal teaching courses and academic development: a collaborative autoethnography. Educational Action Research, 29(2), 328–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2020.1746373

Bradbury, H., Glenzer, K., Ku, B., Columbia, D., Kjellström, S., Aragón, A. O., Warwick, R., Traeger, J., Apgar, M., Friedman, V., Hsia, H. C., Lifvergren, S., & Gray, P. (2019). What is good action research: Quality choice points with a refreshed urgency. Action Research, 17(1), 14–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750319835607

Canto-Farachala, Patricia, & Larrea, Miren. (2020). Rethinking the communication of action research: Can we make it dialogic? Action Research, 20(2), 199–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750320905896

Carr , W. and Kemmis , S. (1986) Becoming critical: Education, knowledge and action research, London : Falmer

Coghlan, D. (2019). Doing action research in your own organisation (5th ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Cornish, F., Breton, N., Moreno-Tabarez, U., Delgado, J., Rua, M., de-Graft Aikins, A., & Hodgetts, D. (2023). Participatory action research. Nature Reviews Methods Primers, 3(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43586-023-00214-1

Heikkinen, H. L. T., Huttunen, R., & Syrjälä, L. (2007). Action research as narrative: Five principles for validation. Educational Action Research, 15(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650790601150709

Hope, K. W., & Waterman, H. A. (2003). Praiseworthy pragmatism? Validity and action research. In Journal of Advanced Nursing (Vol. 44, Issue 2, pp. 120–127). https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02777.x

Jensen, I. B., & Dikilitas, K. (2023). A scoping review of action research in higher education: implications for research-based teaching. Teaching in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2023.2222066

Kemmis, S. (2009). Action research as a practice-based practice. Educational Action Research, 17(3), 463–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650790903093284

McNiff, Jean. (2013). Action research : principles and practice (3rd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203112755

Nehez, J. (2024). To be, or not to be, that is not the question: external researchers in emancipatory action research. Educational Action Research, 32(1), 90–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2022.2084132

Newton, P., & Burgess, D. (2008). Exploring Types of Educational Action Research: Implications for Research Validity. In International Journal of Qualitative Methods (Vol. 7, Issue 4).

Norton, L. (2009). Action research in teaching and learning: a practical guide to conducting pedagogical research in universities. In Action research in teaching and learning: a practical guide to conducting pedagogical research in universities. Routledge.

Riedy, C., Parenti, M., Childers-McKee, C., & Teehankee, B. (2023). Action Research Pedagogy in Educational Institutions: Emancipatory, Relational, Critical and Contextual. In Action Research (Vol. 21, Issue 1, pp. 3–8). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1177/14767503221150337

Leave a comment