In my talk for AdvanceHE today, I tried to offer some principles for navigating this moment of AI change while also considering what the implications of change are for learning, teaching and assessment in HE.

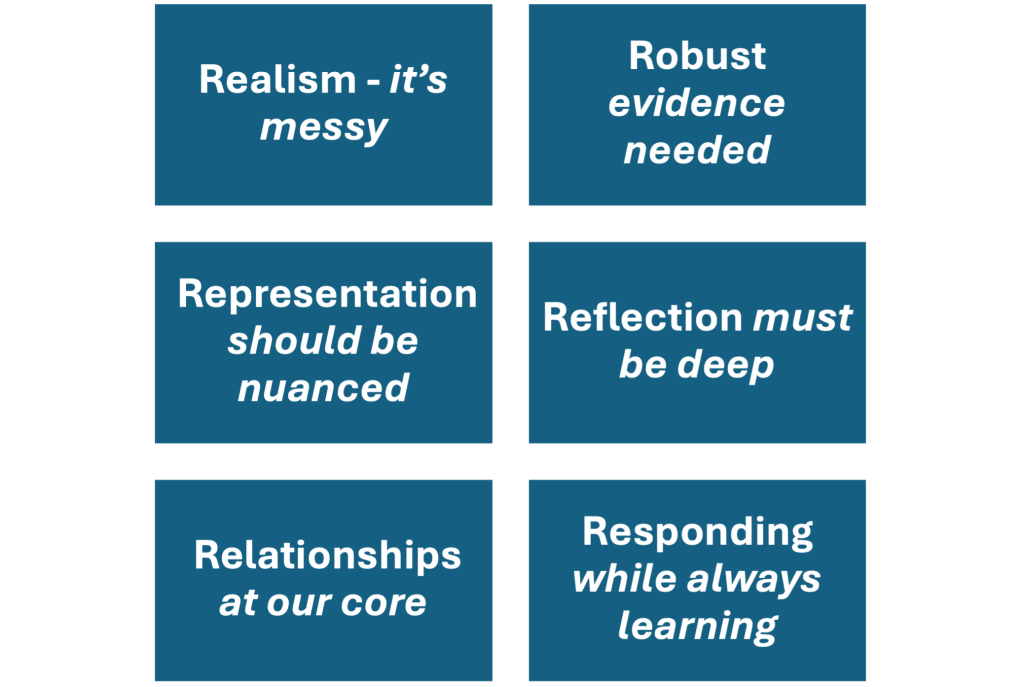

Here are the six points …

Principle one: Realism (the messy kind)

It is a time of significant change and disruption. The first thing I did was draw some parallels with a time that some of us remember, when the internet arrived as an undeniably disruptive force at the turn of the millennium (I know it appeared earlier than that but it was around 2000 that it became game changing). It was a time of great optimism, but also a time when there was a lot to do and even more to figure out. It felt so similar to now.

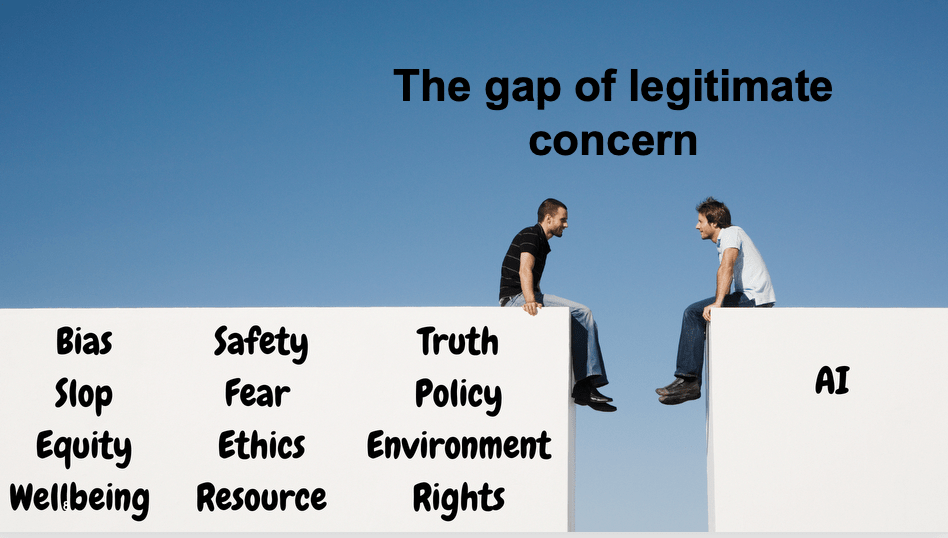

We (as in higher education, but also others) are now working through what AI means for us, trying to hold on to moments of optimism alongside a need to be critical, as we should be. When I talk to colleagues and students, the hopes and fears are clear. There are concerns about the environment, equality, bias, ethics, threats to human creativity and the outsourcing of thinking, and much more. All totally legitimate. And this sits within a much wider context. The world around us is shifting and economists remain divided about the impact AI will have. Some talk optimistically about the range of new high skill jobs that will emerge. Others predict smaller gains. Some even suggest disproportionate negative effects on more vulnerable groups. It is confusing, and there is no single agreed narrative.

What we do know is that governments are developing AI strategies. What is particularly important for educators is that, whatever the stance or emphasis of these strategies, they all have implications for education. Workforce development, training AI professionals and adapting curriculum feature everywhere. In the UK, for example, schools are being encouraged to implement AI curriculum content, while the Nepalese strategy focuses on training 5000 professionals. Change is coming at global labour market level, national level, school level and through professional bodies.

And to add to this, if we look across the last twenty-five or more years, the public conversation around tech in education has not settled either. Headlines from 2001 worried that the internet would damage children’s ability to learn. In the 2020s very similar headlines reappeared, this time asking whether technology is having a negative impact in classrooms. Even the recent and ongoing debates about phone bans tells us that our relationship with technology remains unsettled. Progress on how to work with tech in learning is clearly not linear. We have not neatly resolved the impact of the internet after more than two decades. The technology landscape and implications are are messy lived reality and acceptance of this has helped me understand we need to live with contradictions and uncertainty, and that any ‘solutions’ may be temporary and contentious.The popularisation of AI is the wickedest of wicked issues (I am not calling it a wicked problem, because for me this is opportunity as well as ‘problem’).

Principle two: Robust evidence

Given the number of decisions to make and the many concerns we hold, we need robust evidence. Take the environmental impact of AI as an example. Social media is full of unsubstantiated claims (I can’t tell you how many fluffy animals I see online with headlines about AI impact, but with no linked data). The concern is valid and I take nothing away from that, but the lack of rigour is troubling. Work from Catherine Baker at JISC in 2025 is helpful here, comparing the environmental impact of everyday AI use with other digital activities like video streaming.That type of nuance matters. As we face ethical, environmental and educational questions, we must truth tell and build evidence in a careful and quantified way. We also need to encourage students to use evidence as they form positions that may shape their own choices and engagement. Emotional responses matter, but evidence is critical.

Principle three: Representation with nuance

We need to think carefully about representation. Who is talking about AI? Who is represented? Whose voice is absent? It is easy to treat representation as a headline, something we need to be conscious. It is much harder to examine it in detail. Take neurodiversity as one example among many points of difference. Evidence shows neurodivergent individuals have been found to hold higher levels of satisfaction using generative AI for everyday work. That is understandable when traits such as inattentiveness or struggles with accuracy come into play. Yet if we ban tools, who loses out? Where might we inadvertently disadvantage groups already facing challenges? We also know neurodivergent learners may have higher risks of over reliance on tools (see Horvat and Horzat, 2025). And we know that learning systems in development risk reproducing existing norms rather than accommodating ways neurodivergent learners might prefer to learn. Which means bias is baked in at the design stage. Or consider gender. Women are underrepresented in AI leadership, research and datasets. We often state this fact. But are we really exploring what it means when our students use or critique AI? Which perspectives are missing? What assumptions are built into the tools? What is AI not giving us in the outputs that fails to see the experience of women. I just use two examples here but the liver experience of many needs to be considered in a meaningful way. Representation needs nuance, detail and care. We need to unpack these issues in our own thinking, in the context of policy and practice, and with students as they use AI or come to their own positionality.

Principle four: Deep reflection

We are not on a single journey to some kind of moment of enlightenment with AI. The internet example showed this. We will dance back and forth with the issues as we try and learn. But dance we must! Reflection must be core to that. This means asking what our current ways of working with AI tell us. Why do students upload papers to be summarised rather than reading them? What does that tell us about our academic codes and how exclusionary they may be? Why do students ask AI to make their writing sound more academic? What does that reveal about the voices we privilege? We can question the curriculum. Is a predefined curriculum too restrictive for 2026? Should we move towards phenomenon based learning? Are traditional learning outcomes still fit for purpose? What about anonymity in assessment? Do our communication norms unfairly advantage some students over others?A nd the bigger questions: what is the role of the educator when so much can be learned independently? What knowledge, skills and values do students need to thrive in an AI world? On this question I am particularly drawn to Wylde Scott’s work in this space with an emphasis on learning to learn, adaptability, creativity and the ability to add value (who couldn’t love a book called Raising Dreamers?) I would add the continued need for strong subject expertise, to scruitinise, research, and truth tell when tech falls short. And the value of knowing when to learn fast and when to learn slow. When to friction max in learning matters, because hard learning is good learning, sometimes. We need confidence to know when to work through the steps of mastery because it matters for the foundation of knowledge and for the human joy of achievement.

After decades of wide engagement with PSF one would hope we were collectively well equipped for reflection! We need to ask what AI reveals about the system itself. I guess the bigger question is what we do when we find ‘the system’ lacking. At a local level we may not be able to fix it all, but small changes will be possible.

Principle five: Relationships at the core

Education is a relational act. I almost always say this in any talk. We build knowledge together. Even in online environments, people seek each other out. We research together, write together. Communities of practice often matter to developing practice. And connections within and beyond the university matter – from professional bodies and schools to businesses and geographic communities. So whether it is to support the figuring out of practice or whether it is about ensuring learning remains socially connected, in an age of AI, I’d encourage reflection on the role of relationships and connection as we navigate this period of change. How do we keep people in the heart of change?

Principle six: Responding while learning

Reflection and connection are helpful, but are not enough on their own. Sooner or later, we need to do something! Assessment in the age of AI is a major pressure point and has been a focus. And in response many people will know the two-lane approach, many may be thinking about authentic assessment solutions or, programme approaches to assessment, as well as policy development. Still, we should treat all of new approaches cautiously and critically and fluidly – Guy Curtis has challenged the two-lane approach, while James Croxford and I started to challenge authentic assessment as a concept and as an AI solution (authentic assessment, an area I have worked in for much of my career, is not a silver bullet). The debates are in full-flow and it’s an interesting time. Scholarship of Learning and Teaching (SoTL) is so important here. Early action research is emerging and in my experience that is a good barometer of what the sector is looking at in terms of SoTL. Papers are coming through on topics such as postgraduate supervision, rubric design, simulation games, preparing for practical classes and AI as a research collaborator. But PedAR tends to share success. Sharing what isn’t working, and critiques, is going to be as important as sharing ideas and ways forward. We should be clear in our SoTL that seeking understanding – of the ‘failures’ and successes- is more important than showing off that something worked. Let’s share the stuff that didn’t work too. As well as SoTL, I would advocate for play. Individually and collectively. Play with tech helps us master the tools and understand them, and doing that together is both enjoyable and informative. It provides experience as the basis for action.

In conclusion

I offer six principles for navigating AI: Realism – it’s messy. Robust evidence needed. Representation should be nuanced. Reflection must be deep. Relationships at our core. Responding while always learning. There may be others of course and this will likely evolve.

P.S. As mentioned in my talk here are a list of references used to inform the session and this post:

Leave a comment