This blog article is written to accompany my presentation today at Jisc’s Digifest event.

Curriculum change at scale is always tricky; first-hand experience, as well as experience working with colleagues at different institutions, shows that challenges can include:

- Finding time for the work

- A lack of programmatic thinking and a focus on modules

- Over complex frameworks and institutional rules which have unintended consequences

- A failure to use curriculum work to anticipate the known difficulties that staff and students experience (e.g. marking peaks, students becoming independent, strengthening critical thinking skills)

- Passionate voices which generate too many actionable ideas (there is so much that could be done with curriculum, but time is not infinite)

- Differences in pedagogic outlook lead to team tensions about how things should be taught

- A failure to engage stakeholders so that curriculum work becomes an insular academic activity

- Exclusion of professional services colleagues who are left to fix the consequences of poor design

- Frustrated resource managers who must adapt to support the curriculum but who don’t always get to input into its shape despite their expertise

- Committee stages in course development can feel cumbersome and frustrating and they may involve too much documentation.

Curriculum development at scale has characteristics of a wicked problem.

The blueprinting method that has been developed at Harper Adams aims by myself, Steve Barnett, Simone Clarke and Lisa Barnett set out to address these difficulties and provide a positive, creative space to allow course teams to develop their curriculum whilst involving planners and resource managers throughout. Here I won’t talk about the specifics of the work we have undertaken in our institutional curriculum review work, instead, I will simply outline the ‘mechanics’ of the blueprinting method. Though the steps are presented sequentially, it is never, in reality, this neat and there is a to and fro between stages. In presenting this method, I need to be really clear that we didn’t execute this perfectly – there was much I would personally do differently; the evaluation of our implementation is another story and one perhaps best told in time by others. This is simply a statement of what we attempted. This is an outline of the methodology.

- Consultation: Asking questions such as what do we want our curriculum work to achieve e.g. improved student independence, more manageability of student support for staff, employability, the design of a curriculum for students who access learning through different modes – the list is almost endless, but the first step is to understand what is needed.

- Framework: For a curriculum to actually function a framework is needed. Consultation and decision-making are key here. What is the credit framework, will there be a common dissertation element, how will academic skills be embedded (is a common approach needed?), what will our assessment principles be (linked to what we are seeking to achieve), and, what are our graduate attributes. Being aware of the implications of decisions at this stage is important, but once decided the process must move on.

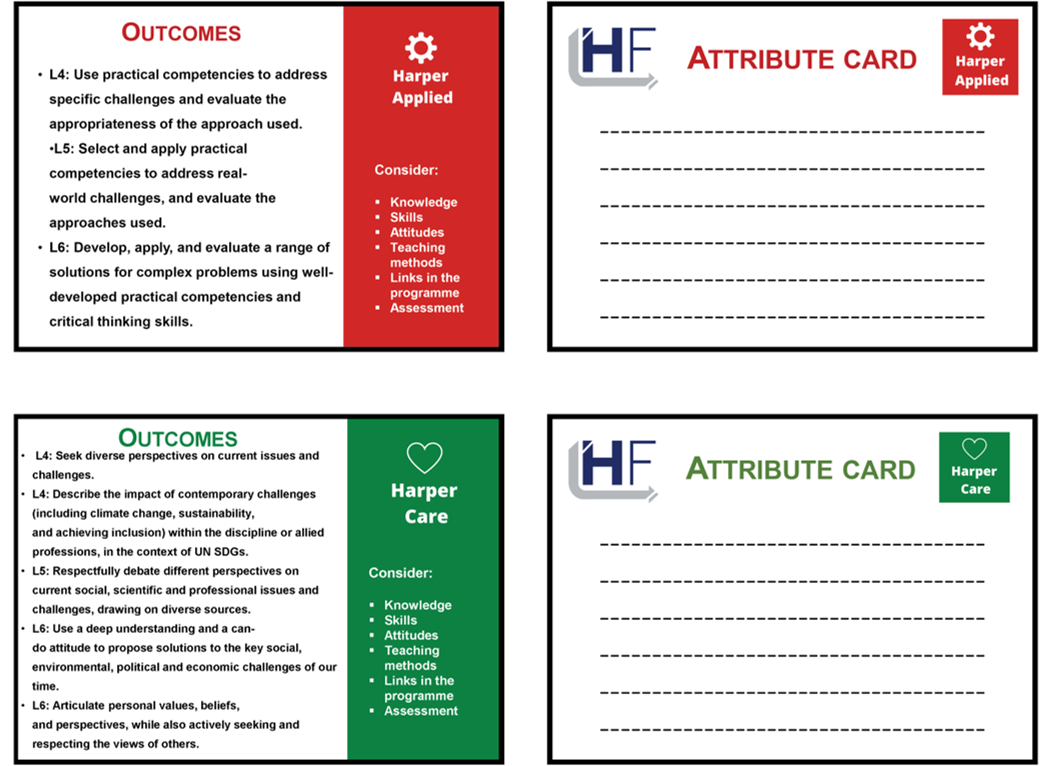

- Attributes: While attributes are subsumed in the development of a framework they deserve a special mention here; attributes should be meaningful, memorable and linked to the essence of what it is to be a graduate of ‘institution x’? For too long graduate outcomes have been a generic list of something resembling key skills – they have been a catch-all. We have reconceived them as the distilled essence of ‘our’ graduates with just six thematic areas emphasised (our six being – applied, digital, global, growth, care and research (known as inspire).

- Team creation: Curriculum teams need to form to ‘do’ the work of development. Diverse teams matter here to avoid groupthink and to encourage rebel ideas. Thinking about diversity in a team may include thoughts about personal characteristics and roles e.g. new staff, professional service colleagues, those who are research focussed, pastorally focussed specialists, subject experts, experienced colleagues and more. I’d encourage that team formation to be open and transparent and for all involved to work against a notion of being ‘in’ or ‘out’ of the group.

- Research: Once teams are formed – research can get underway. There is no rule book for researching a curriculum and each team or discipline area may do this differently. Reaching out to schools (students of the future), charities, alumni, current students, and employers would seem essential components to build up a picture or possibility. Desk-based research on the market aspects can, hopefully, be assisted by colleagues who are specialists in this area. As a follow up on this point one of my colleagues, Dr Lucy Crockford, articulated her perspective of some stakeholder research feeding into this process.

- Minipitch: Committee papers can be limiting in conveying the passion of teams, they take a long time to write and may require detail that is simply not there yet. Replacing the ‘committee’ activity with something more collegial to progress developments is possible. The mini-pitch event involves relevant and responsible committees coming to hear presentations, ask questions and celebrate the work completed. Other development teams and wider teams can come too so that the sharing is open and transparent. Everyone who attends must (as a condition of attendance) give the team feedback that is usable. This event can act as a formal approval point if needed, but it is a celebration, a briefing, a Q&A session, a resource planning check, and critically a feedback moment.

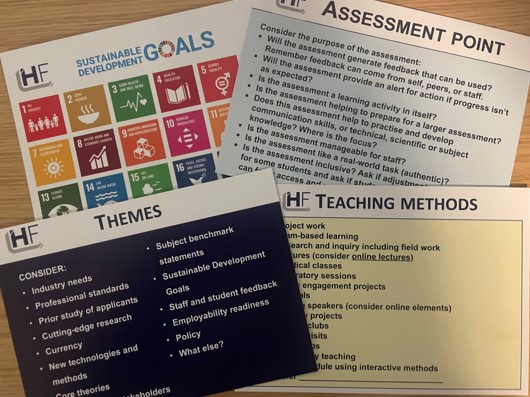

- Blueprinting: A three-day event is held away from the usual place of work. It is critical that colleagues are released from other commitments so that other work can be set aside to give focus. Out of office should be on. Day 1 is vision building – using cards which set out the graduate attributes as well as other cards to provoke thoughts on teaching methods, assessment types and purpose, and content, as well as cards for the UN Sustainable Development Goal, teams use all of their intelligence gathered to map an optimal student journey through a programme. Questions are asked such as – what digital skills are needed and where are they facilitated? Where would feedback be useful? Where are the transition points and how do we support them? The finale of Day 1 is a very big plan/graphic, but really the benefit is in a brokered understanding of a shared vision. The product is less important than the process. On Day 2, the vision becomes more focused on the creation of a programme specification document. Teams agree on how to articulate their vision in a way that others will understand. At this point module name placeholders are created. On Day 3 we move from programme to module-level thinking, and each of the placeholder modules is commissioned. The people in the commissioning team may or may not write them, but there is an articulation of what the module needs to do to contribute to the programme. This can be done by a simple template form, where the team articulate how the module can meet or support attributes, any specific features of pedagogy that should be considered, what the module is doing in terms of the programme, and any key content that is envisaged. This is a tricky balance between commissioning modules that fulfil the programme, and which also leave enough space for others to add influence and flair. Once commissioned, module writing and the documentation formalities can be finalised. With their permission some colleagues have allowed me to share some of the benefits they felt from the days spent on this activity – critically though these are snapshots and a full evaluation is still needed.

- It was good to be in a collaborative team with the time and space to discuss ideas. Being ‘away’ from campus encouraged this sense of freedom to explore.

- Planning for thematic flow throughout the degree programme. Repetition, overlap and disjointed and discombobulated discrepancies can be avoided by blueprinting in this manner.

- Having the space and time to discuss things without having to juggle other things Everybody having a chance to make their suggestions, and listen to other people’s suggestions

- Reach out: Work then needs to be undertaken to translate the blueprinting into a team vision. This can be done as a one-off event but better that it is done throughout the process with all members of the curriculum team liaising, communicating, and seeking feedback, so that after the event days, everyone has some ownership and involvement.

- Operationalising: validation is not the end – roll-out is essential! Alongside other stages, but also after modules are complete, systematic and conversational engagement can occur with stakeholders. Asking ‘who supports and enables the curriculum?’ leads to a long list from IT colleagues to library specialists, and from facilities managers to timetabling colleagues. Brokering a mutual understanding of how services and facilities can support future curriculum can occur through, and be enhanced by discussion. Setting up an operational channel to trigger discourse means that a two-way engagement happens – course teams have more appreciation of operational constraints and managers can gain more appreciation of what is needed.

This is the method that I have shared today at Jisc’s Digifest #Digifest23 event in hope that it encourages others to consider how we can achieve programme-level planning which also addresses some of the challenges of curriculum development work at scale. No doubt there will be more to follow as the story unfolds …